Ars longa, vita brevis

When someone dies you start to get to know them in a different way. Selfishly you acknowledge that they are no longer there for you, not available to furnish you with a reflection of yourself. I now start to understand Mick Farrell through his art; his modesty and generosity having previously prevented this. And, ever artistically selfish, I see parallels with my own artistic trajectory in relation to certain aspects of his production, namely repetition, collage, experiment and the period in which he made the work.

Farrell’s early training and foundation as a stone sculptor reflect a desire to wrestle with solid, impacted earth and matter in order to expose and create new forms that echo both the natural and manmade world. In this work there was also a sense of ‘art for the people’, art in public places and for the benefit of all. The relationship with physical form morphed into his own brand of three-dimensional photographic sculpture. A large sewn ‘photo-carpet’ entitled, Grill, was shown in the Whitechapel Open and this piece was a testament to his patience, inventiveness and ability to jump the boundaries of convention.

Farrell was part of a broader creative unconscious producing sewn photographs synchronous with other photographic innovations. Photography had undergone another renaissance in the early 1980s, eschewing the purely documentary and rediscovering its roots as a new art discipline. Warhol too was sewing, he had appropriated the stitched photograph concept from his friend, studio assistant and travelling companion, Christopher Makos (1). Farrell’s stitched photo-piece heralded a new era of artistic practice and consequent works expand into rich experimental photographic works. These further reference seminal exhibitions such as Peter Bunnell’s 1970, Photography into Sculpture (2) presented at MOMA, New York, particularly works such as Multiple Solution Puzzle (1965) by self-described ‘paraphotographer’ Robert Heinecken.

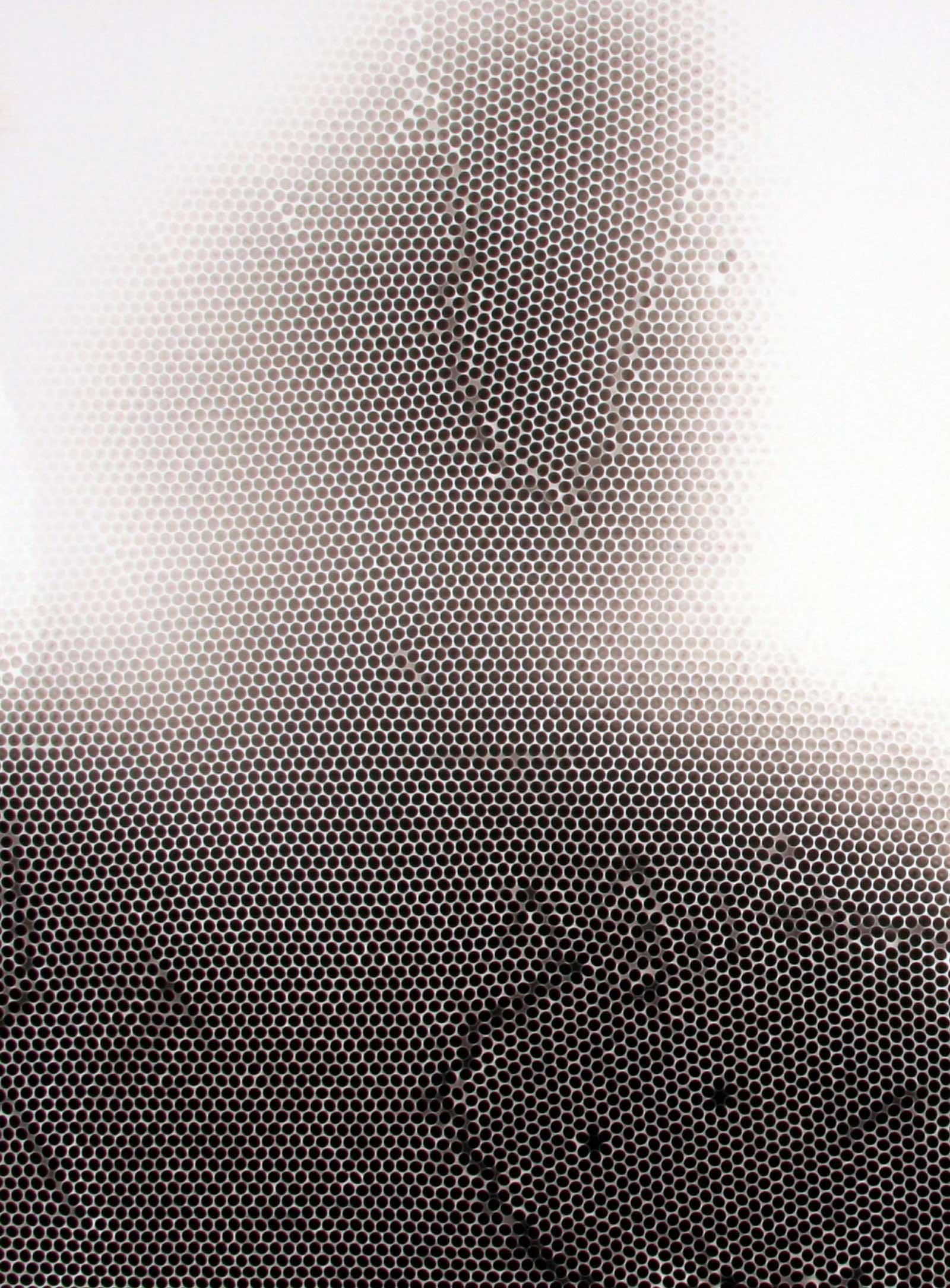

The straw camera works date from 2007-9, and were made in collaboration with Cliff Haynes who also worked at the Slade School of Fine Art. These are unique and fascinating not only as records of an unusual and highly original photographic method of creating pictures, but also because, by virtue of the simple drinking straw, they combine the handmade and the mechanical with a playful approach to the ever flexible medium of photography. Our attention is drawn to the inconsistencies of surface patterns produced and the glitches recorded by the physical construction of the camera, these bestow a unique characteristic on the results. Our brains struggle to collapse the space between the knowledge of the process and the reality of the images created.

This strange contribution to the canon also relates to photographs by Madame Yevonde during the 1930s when a series of zany Vivex colour images (3) streamed out of her studio. This contemporary ludic work rearranges still life objects into compositions that also manipulate the obligatory skull, vessels, fruit and flowers of memento mori paintings. The mannequin equipped with headscarf drape immediately conjures pictures of Jackie O minus the sunglasses. This series of works updates the medley of stalwarts; fruit and beach ball, flag and teapot, elements juggled to satisfy the loose credentials of that genre while still embracing open creativity. The mantra could have been Yevonde’s (4) - ‘Be original or die!’ as this same attitude underpinned their photographic forays into the unknown. These artists were avid to try new ways of colour composition and techniques, recycling their props, as artists have done from time immemorial, recalling the yellow velvets and ermine that recur in Vermeer’s paintings.

The ‘straw’ portraits in colour are fresh; sitters literally aglow in vibrant hues. The colour shifts have an aura of rainbow solarisation, their unusual combinations rendering them simultaneously beautiful, surreal and spooky. A palpable sense of happenstance is encased in these eloquent and timeless portraits. Typically half-hidden, Farrell emerges in a lone self-portrait sharing the picture plane with the disembodied polystyrene bust making this particular work in retrospect all the more poignant.

There are connections with Patrick Tosani’s (5) braille portraits, however his appear as inversions of the early black and white soft focus straw studies. In the former the mechanised holes punch outwards, in the latter the hand set rows of straw-filled light spots are part of the construct, they are the formal building blocks that create the sitter. Unlike the colour photographs, the black and white portraits reverberate like luminous yet vague presences that hover semi-solid amongst the miriad rows of punctuated light. These pinpricks constitute the whole massing together of the sitter, each one an integral part, so different from Tosani’s disconnected blank vision.

These images are solid and yet retain a ghostly, mysterious presence locked within their strange methodology. The works operate like records of an out of body experience, uncanny but real, thin as photo paper but palpable as people fixed in a magical and curious conundrum space.

This is the beauty of art and artists - we can speak from the dead to both the living and the dead. Mick Farrell continues his generous conversation with us from over on the other side and we continue to formulate our answers in response to him.

Life is short but art survives

Notes

1. According to art historian William Ganis

2. MOMA event and the subsequent MOMA exhibition

3. See Colour and the Vivex Process

4. See R.Gibson & P.Roberts, Madame Yevonde, Colour, Fantasy and Myth, NPG, 1990

5. From 1985, see Patrick Tosani